Stories

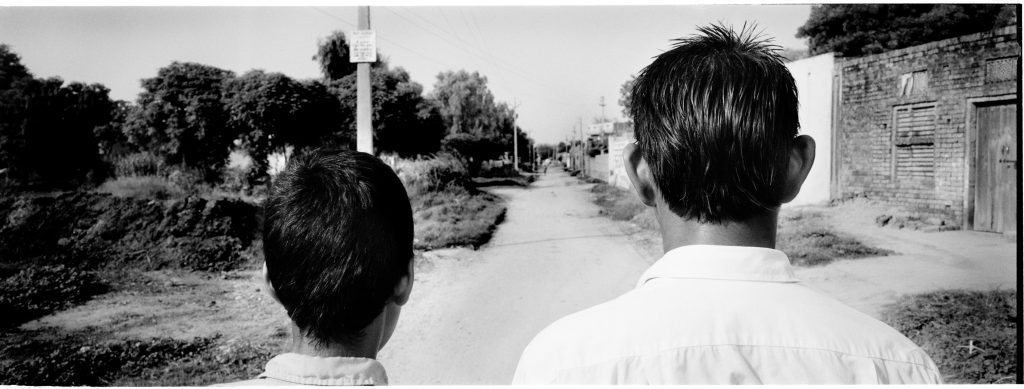

Punjab

SUICIDE AND PESTICIDE – CRISIS IN THE PUNJAB

Punjab, a state in Northwestern India with a population of almost 30 million, has, over the last 45 years, gone through an agricultural transformation.

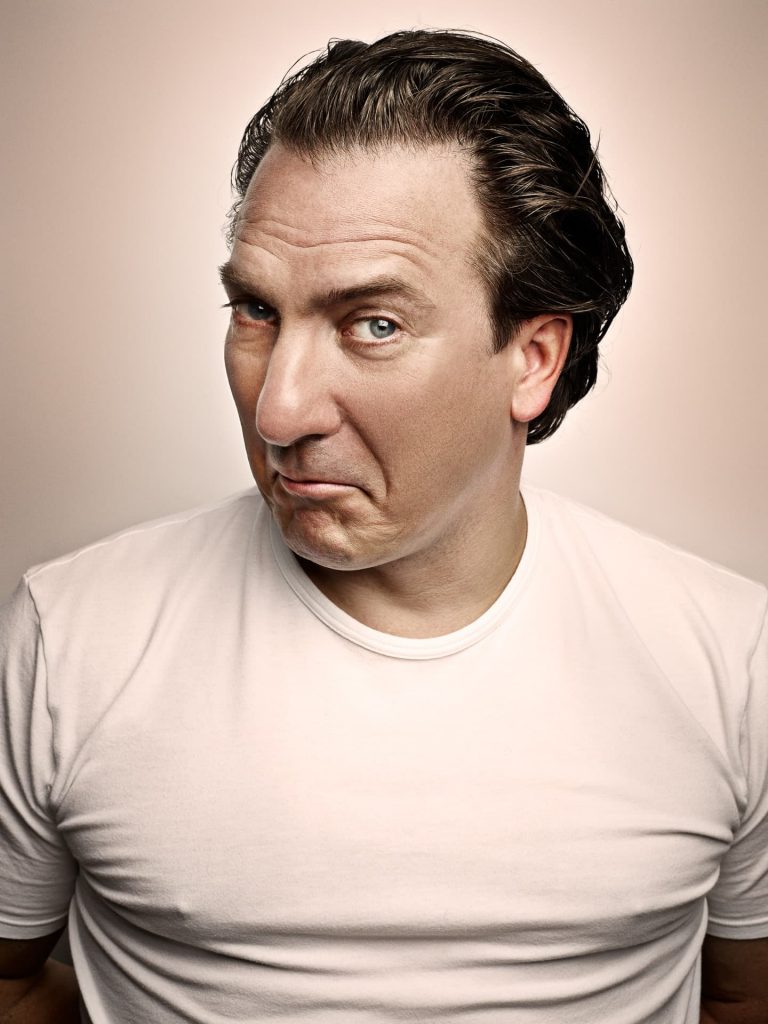

verena

altenberger

„Ich kämpfe ständig

gegen das große Scheitern an“

Verena Altenberger macht keine halben Sachen: Für die Hauptrolle als heroinsüchtige Mutter in Die Beste aller Welten recherchierte sie in der Salzburger Drogenszene und baute über Monate eine intensive Beziehung zu ihrem Filmsohn auf.

new

europeans

A Long Way Here: Portraits

of New Europeans

A giant migratory wave washing over the shores of Europe. A massive influx of refugees. A swarm of foreigners.

desert

water

Desert Water – The Curse of the Tigris

“Nothing in the world is more flexible and yielding than water. Yet when it attacks the firm and the strong, none can withstand it, because they have no way to change it.” – Lao Tzu